ECE

Cover Artwork Submissions

Cover image

Cover image

Ashlynn Miles, Griswold High School

Underwater

A painting of a woman in a white dress underwater using a type of medium called guash. This artwork is a symbol of transition and moving forward. It represents stepping into something new. A new perspective, its own glow and scope of color. It represents a feeling of weightlessness where gravity does not apply and the world is muffled and silent.

Runner up

Runner up

Nicole Gallecher, Bolton High School

Flying Through Colors

When given a transitions assignment I automatically thought of the lifecycle of a butterfly. I started by sketching the branches, next the caterpillar, then the cocoon. I filled in each with a variety of colored pencils. After that I sketched the butterfly and added the color. Finally I included black marker to outline the butterfly and branches, and add in more detail to the cocoon and caterpillar.

Investing in Continuing Education

By Stefanie Malinoski

With close to 1,500 certified UConn ECE Instructors as part of the program, UConn ECE follows a thorough certification process to review and vet all applicants. All certified Instructors through UConn Early College Experience must meet the rigorous certifications standards set by each University Department that we work with to offer UConn courses in our partner high schools. These certification standards are the same standards used when hiring adjunct faculty members to teach the courses on campus. Many disciplines require a master’s degree in the content area in order to qualify for certification. Other disciplines may accept a master’s degree in Education, with a bachelor’s degree in the subject area and two or more content-based graduate courses in the appropriate discipline. But what happens when a motivated teacher may fall short of the Department’s standards for certification?

In 2007, UConn ECE began a scholarship program to assist current high school teachers who are looking to become certified to teach UConn courses in their high schools. Currently, UConn ECE offers two scholarships each semester — Fall, Spring, and Summer — to teachers who are interested in UConn ECE certification. The scholarship allows interested teachers to take graduate courses or necessary undergraduate courses in their content areas at any college/ university to become more qualified candidates for certification.

To date, almost 60 scholarships have been awarded to high school teachers helping them achieve certification with UConn Early College Experience. After many years of classroom teaching  experience, it can be daunting for teachers to transition back to a student role. However, it is clear we work with dedicated teachers who exhibit the willingness to go the extra mile to offer UConn courses at their schools and build their professional resumes. Their commitment to complete additional coursework is indicative of their superior education and tireless efforts found at the high school.

experience, it can be daunting for teachers to transition back to a student role. However, it is clear we work with dedicated teachers who exhibit the willingness to go the extra mile to offer UConn courses at their schools and build their professional resumes. Their commitment to complete additional coursework is indicative of their superior education and tireless efforts found at the high school.

For some instructors this is a process that may take a significant amount of time. In 2018, Seth Murphy (Thomaston High School) inquired about the possibility of becoming certified to teach UConn’s POLS 1602: Introduction to American Politics. At the time, Seth was already certified through UConn ECE to teach U.S. HIST 1501 and 1502 (2018) but was looking to expand his certification to include other courses so they could be offered to the students at THS. Based on his unique background and interests, he believed he would be a good fit for certification to teach additional UConn courses in European History and Political Science through UConn ECE. After his transcripts and application materials were reviewed by the Faculty Coordinators from European History and Political Science, they determined additional coursework would need to be completed in each discipline before certification could be reconsidered. While some teachers may be unable to dedicate the time or have the ability to complete additional coursework, Seth set out on a plan to complete graduate-level political science and history coursework so he could achieve certification in the future.

In 2020, after two years of completing graduate level coursework and utilizing the UConn ECE Graduate Scholarships, Seth achieved certification to teach HIST 1300, and 1400 and POLS 1602 in 2021. Seth says “The scholarships have allowed me to offer my students up to fifteen college credits. When I started at my school the only UConn history courses, we offered were 1501 and 1502, but now they have five different classes to choose from. I am proud that, by taking my classes, my students can earn an entire semester of college and be one step ahead of the game.” As of the 2021-2022 year, an entering freshman at Thomaston High School now has the ability to earn thirty-four UConn credits throughout their academic careers at THS. Seth shared that students can graduate high school and enter college with enough credits to be considered second semester sophomore status.

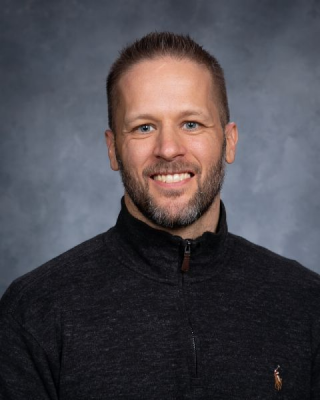

Instructor of Distinction: Kevin Mariano

By Brian A. Boecherer

Q. How long at Plainfield High School?

A. I am currently in my 14th year of teaching, all at Plainfield High School.

Q. Which courses do you teach?

Q. Which courses do you teach?

A. I co-teach the Social Studies side of American Studies with Ms. Laura Maher who teaches the English side. I also teach Modern World History (10th grade) and a self-designed course entitled “Dialogue and Rhetoric” for grades 9-12. This immersive class is designed for students to refine public speaking skills and build empathy with one another to create a safe environment to hold meaningful dialogue conversations and deliberate compromise in a civil way. I also coach our competitive Debate Team and am the Director of the Fall Drama and Spring Musical Theater

Programs.

Q. Tell us why you got into teaching and maybe a bit about how you see your role as a teacher?

A. In 8th grade I considered being a teacher but thought it would be boring to do the “same thing every year for 30 years.” As I headed to college to study international relations a year after 9/11/2001, I considered becoming a US Diplomat to bring peace and healing to our country. Above all else, though, I wanted to be a dad someday. After some soul searching during my first semester of college at the University of Maryland, I knew that “I didn’t want to be a dad who was home for three weeks and traveling for three weeks.” As such, history was “what made sense to me” and I ultimately wanted to “help kids now to encourage peace for our future.” Teaching high school students has been a dream come true; building a rapport, earning their respect and bonding with students is the skeleton key to my job. Those moments fill me with joy. I am happy to inform my 8th grade self that teaching is “30% lessons and 70% psychology”, meaning that each moment matters and if I am bored, I am not doing my job the right way. And, I am never bored.

Q. You won the Teacher of the Year Award last year at Plainfield High School and were a semi-finalist for the Connecticut Teacher of the Year this year. What would you say is core to your teaching philosophy?

A. I strive daily to build a genuine rapport with my students and faculty based on a single philosophy from Lakota Chief Crazy Horse’s statement, “We do not inherit the Earth from our Ancestors; we borrow it from our Children.” These connections are the foundation to building kind, empathetic, and self-confident humans who move on to help others in their lives. Upon reflection, this has been a pillar to the application of my philosophy. Our Debate Team was built from my (seemingly) bold decision to do “that” with “those kids” as some naysayers once taunted. The Team proudly competes in the annual Dr. Grace Sawyer-Jones Parliamentary Tournament held at Three Rivers Community College and consistently does well, winning the 2016 Championship. During remote learning last school year which paused the competitive Debate circuit, the Debate Team students connected to fellow students by creating “Panther Break Out Rooms” each Wednesday for eight weeks. Earning administrative approval and adding a link on the school website, Debate Captain Julia Koski reflected, “I learned about the power even single individuals have to cultivate change.” In sum, empowering students to help others is the zenith of our profession. Inspired kids inspire kids.

Q. As a UConn ECE Instructor of American Studies with your co-teacher Laura Maher, what sorts of things do you want the students to walk away knowing, so when they reflect on your class 20-years from now they still know?

A. In 20 years, Laura Maher and I want the students to realize that history will most likely repeat as we profess that American history is cyclical and our Forefathers’ generation battled similar issues that we negotiate today. Our aim is to engage the students to “destroy the box, build your own box, then constantly try to reshape it.” Never settle and always be working to “build a more perfect union for our posterity.”

Neither of us ever learned about “the present day” in depth while in our high school US history classes. Therefore, our first unit in American Studies revolves around the Obama and Trump presidencies, including, but not limited to, the impact of various social and political movements like Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter. Our students are hungry to discuss and learn about these topics. They see it daily playing out on social media and in the news, and they plead to have dialogues about “things that matter.” We explore varying perspectives with the students, and have had guest speakers including a professor and a police officer educate our students on how political and the media’s rhetoric influences their lives/jobs and how, in the end, the “goal of the movements is to achieve the same thing.” Meanwhile, the students dissect the Broadway musical Hamilton as a form of historical and modern-day commentary, casting another light on immigration, women’s studies, and building “a more perfect union.” In sum, as we cover American history dating back to the 1920s, we are constantly making connections to the modern era, so the students can better understand

the “cause/effect” of an era and determine for themselves to what extent progress has been achieved. Moreover, Laura and I stringently target the quality of student writing over the entire course and assess the students on their

ability to set new goals for the next paper (and to what extent they achieve their goals). Through all of this, students will hopefully appreciate their steadfast hard work, better understand the world they have been dealt, and feel confident to use their voice to impact our world for the better.

Q. We are living through some difficult social times, but Americans have lived through other difficult social times and come back stronger. Do you have any advice for the everyday person on how to play a part and make things better?

A. Americans have lived through many turbulent times, but never in the social media age. To just think that the political landscape will magically improve on its own is dangerous. Many of us have created our own worlds on our phones, liking and unliking, following the news we want and ignoring the news we may consider “fake” or disingenuous. While “yellow journalism” is not new, the “war on the truth for-profit” is cancerous, and today’s generation of students are, by far, the most SKEPTICAL that I have worked with in my career. Across the board, they appreciate that they are American, but know that adults in our society could set better examples of living up to the standards and ideals of this “City upon a Hill.”

To this reader, I assure you that this generation of students is watching the adults’ every move on the issues that mean the most to them: #1 climate change, #2 gun rights/violence, and #3 treatment of marginalized populations. This generation of youth is also the most inclusive group in terms of accepting people for who they are. For most teens, they want adults to know that technology is their friend and their catalyst to progress. Following the news daily can bring us to a dark place, which is why it is important to focus on the things we CAN control. In the classroom, I insist, “Make our world a better place by making your world a better place.” How? 1. Always help someone. You might be the only one that does. 2. Everyone you meet is struggling with something all of the time and it is normal to ask for help. 3. This world will be more peaceful if we listen to understand and act to compromise rather than remain tribal.

2021 UConn ECE Scholarship Winners

UConn Early College Experience recognized 10 outstanding UConn ECE Students this year, awarding each a $500 scholarship, which can be used at any institution. Winners are high school seniors, who have taken or are currently taking at least one UConn Early College Experience course and have excelled in the area in which they submitted their project. Learn more about the UConn ECE Student Scholarships on our Scholarships page.

Excellence in the Arts, Humanities, or Social Sciences

Winners demonstrate academic achievement and a potential for future academic and professional accomplishments in a field focusing on the Arts, Humanities, and/or Social Sciences.

Emily Tarinelli

Marine Science Magnet High School of Southeastern CT

Literary analysis essay: Feminism in the Absence of Independent Women

Ayushman Choudhury

Ellington High School

Rhetorically effective argument video: The True Cost of War

Kiersten Sundell,

Thomaston High School.

Portrait: Am I Next?

Excellence in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematic

Winners demonstrate academic achievement and a potential for future academic and professional accomplishments in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and/or Mathematics.

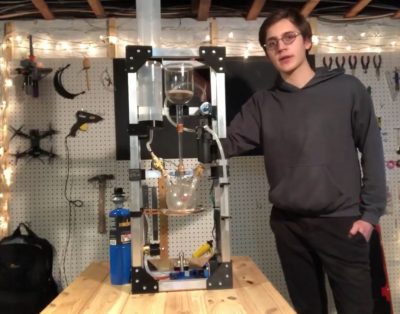

Conner Larocque

Hamden High School

Video: Autonomous Siphon Coffee Machine

Grace Pendleton

The Morgan School

Model: Gothic Cathedral

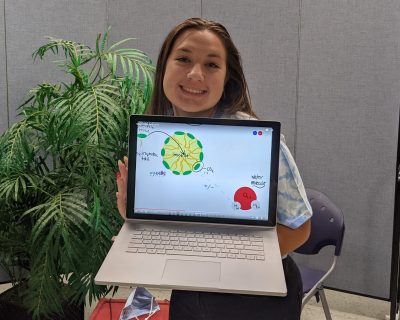

Emma Bator-Blanchet

Rockville High School

Video: How Soap Kills Coronavirus

Excellence in Civic and Community Engagement

Winners are academically successful, are already making a positive difference in their town or neighborhood, and are inspiring others to do the same. The students chosen for this award must be a UConn ECE Student who demonstrates ambition and self-drive evidenced by outstanding achievement in both school and their community.

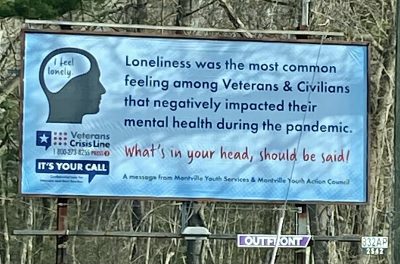

Stephen Duhamel

Montville High School

Development and promotion projects that strengthen peer interactions and wellness

Lindsay Haukom

Edwin O. Smith High School

Quaraconcerts, free virtual harp concerts offered to anyone who wanted happiness and human connection

Matthew Keating

Holy Cross High School

Co-founder of Step by Step, a nonprofit organization that helps the less fortunate in the community

Anirudh Krishnan

Ridgefield High School

Founder of the Ridgefield Music Mentors program

Photos: Finding Joy, Finding Beauty, Finding Purpose.

By Elizabeth Kindt

The artist who photographed the cover of this summer’s 2021 UConn ECE Magazine is UConn ECE student Cindy Santiago from New Britain High School. Cindy’s photograph titled “Tulips in the Springtime” was a photo taken during the month of May that reminded her of Copenhagen. In her submission Cindy writes that Copenhagen has, “the prettiest fields full of tulips which is what inspired me to take this photo. I made sure to angle it in a way that makes you look like you’re inside the field in a way.” Congratulations to our cover artist Cindy, and thank you for finding the joy and beauty in our Springtime Submission Contest.

Thanks to all who submitted photos and congratulations to the follow students whose photos appear in within the pages of the magazine:

Brian Carson, Seymour High School. The focus within the many. White flowers on the branch of a tree. One is in focus, despite them all being nearly the same, this sole flower is the most beautiful.

Jada Vercosa. Southington High School. Watch sweet magnolias in bloom! Magnolias are a beautiful flowering tree and the blooms are so delicate. The light pink color and petals can be seen where I live and they always make me smile.

Alessandra Sanchez. Montville High School. Pretty Little Thing. Just saw an email about this and I love photography so enjoy 🙂

Janeesa Libanori. E. C. Goodwin Technical High School, Life is like a flower, plant the seeds and watch them bloom. As life begins, the “flower” gets watered and grows. This refers to babies growing up into young adults and as they grow, you watch them bloom. Parents teach their children how to grow up and strive on their own.

Srilekha Kadimi. Amity Regional High School. Live Life In Full Bloom. Fully blossomed magnolia.

UConn Geoscience: Earth’s Dynamic Planet

By Robert Thorson, Ph.D., Department Head

and Faculty Coordinator, Earth Science

We know that high school and college students are manifestly anxious about the current climate crisis. But how many also know that Earth isn’t fragile? That climate comes from underground? That ecology is only one part of earthly operations? That radioactive decay keeps our planet habitable? That petroleum is no less natural than water? That oxygen was originally an exhaust gas pollutant? That humanity’s most expensive mistakes involve ignoring the deep time of planetary history?

NASA Image of Earth from the International Space Station. Reid Weisman, Sept. 4, 2014.

It’s an ongoing and societally expensive tragedy that few U.S. citizens know how the Earth works as the whole pie, rather than pieces carved up into arbitrary disciplines. Typically, they were taught only nuggets of old-school geology in grades 8-10, rather than the mother lode of new school geoscience that remains undiscovered for most. I call this new school “whole earth environmentalism”, the idea that understanding how the planet works as a beautifully coherent integrated system is a prerequisite to best-practice management of the specific environmental problems that capture media attention.

UConn ECE is now offering an opportunity for students to learn about how it all works with a course that educates and also puts them on a pathway to important careers that will make a difference.

Meghan Kinkaid, UConn ECE Instructor from CREC’s Academy of Aerospace and Engineering, is a pioneer. This past year, she was the first instructor in Connecticut to offer UConn’s popular introductory geoscience course Earth’s Dynamic Planet (GSCI 1051). Her students now know that they are “impacted by geosciences daily and that this course gives us an opportunity to make them aware, take interest, and possibly plan a career around it.”

They’ve also learned that good jobs, high salaries, and rewarding careers are increasingly available, given the near-future shortfall of 175,000 geoscientists estimated by the American Geosciences Institute. Beginning with this UConn course offered through UConn ECE, the vast majority of UConn’s geoscience majors following one of three tracks (Earth, Environmental, Atmosphere) go on to successful scientific careers: mitigating natural hazards, improving risk assessments, restoring landscapes, accessing clean water, obtaining mineral resources, developing geothermal energy resources, science communication, and education.

The other high school teachers in Meghan’s pioneering cohort of UConn ECE-certified instructors—Lewis from the Hartford Magnet Trinity College Academy and both Christopher Tait and Harold Condosta from Ridgefield High School—were ready for takeoff last fall, but the chaos of the Covid-19 pandemic forced their administrations to delay. Five high schools, including New London High School and Plainfield High School, have certified instructors. Next year, four schools are scheduled to offer GSCI 1051. With school returning to in-person for the fall, Meghan McNichol (New London High School) quipped, “we won’t have to work twice as hard to accomplish half as much.”

Though Meghan Kinkaid is our pioneer, Kim Glazier, a science teacher from Plainfield, is our visionary. “Going forward,” she wrote, she “would like to see all of our AP classes replaced with ECE options.” AP or Advance Placement courses are those which high school students master content to “test out” of a college course during a grueling three-hour exam, provided the college accepts them, and they get a high score. UConn courses taught through UConn Early College Experience are those where the students experience the actual college course being taught in the comfort of their own school by a familiar teacher being supervised by a caring university or college faculty member. Kim’s vision aligns with our growing awareness that sit-down standardized testing is less accessible to under-represented groups, and less accurately reflects the diversity of approaches needed for STEM science careers. When reviewing the GSCI 1051 course description, Kim realized that UConn’s Earth’s Dynamic Planet “would meet the requirements of our required Integrated Science class and thought it would be awesome to offer a course that can lead to college credits for something the students have to take anyway.”

During our inaugural UConn ECE workshop of May 26, 2021, six of us—Meghan, Meghan, Jared, Harold, and me (with Kim included later)—bonded as a team dedicated to increasing the quality of geoscience education in Connecticut high schools. We invite you to join us by reviewing the GSCI 1051 course that unites us and contacting any of us for more information. As UConn’s ECE Coordinator for Geosciences, I’m a good first contact. I look forward to hearing from you.

Unsourced.

NACEP Re-Accreditation – An Editorial Not a Description

By Brian Boecherer

By the time you read this article, the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment Partnerships (NACEP) Re-accreditation application will have been submitted. Almost 900-pages of paired syllabi, assignments, statements of equivalency, analysis, documentation, and testimony from the four-corners of the program and the highest levels of the University. This has been my third time engaging in NACEP accreditation, with my first time in 2006 when UConn Early College Experience entered into its modern renaissance. When you complete a task as big as accreditation it feels important in many ways. No matter how experienced you are in the program, after leading an accreditation effort, you feel more knowledgeable than ever before. You have synthesized huge volumes of information, have lead many professionals in a very detailed way, and have created and edited hundreds of documents until you feel they are perfect. You are ready to lead the next chapter of the program, because you see how complete some areas are and where new opportunities should develop.

NACEP accreditation makes me very proud. Not only because we have the status of third-party review, but because our program shines in ways that few other programs do in the nation. As you have heard time and time again, UConn ECE is the oldest concurrent enrollment program in the nation. It is also really one of the best too. We are seen by others as an ivy league in terms of concurrent enrollment. Like the character of every person, our collective and constant efforts make us who we are. We are passionate and dedicated. We work hard and value the fruits of our labor. We care. This is not only true around accreditation time; it is true every year, all the time.

I remember when I started with the program full-time in 2005 (having really started with the program in 1999) and setting the development plan for the office through a process of visiting all the high schools in the program to learn what we did well and where we needed to improve. The high schools and the departments—our great community—put the issues on the table and we ran with them. NACEP was an important part of that story, because it helped us set goals, meet them, and then we aspired to surpass them. The drive to surpass them is part of our character and we should all be very proud to be part of that story.

As the director and the curator of the NACEP application, I know our re-accreditation package will be well-received. I also know that it took a community to create. It is the UConn ECE Community that creates the program, the accreditation package is a recording of your fine work. Thank you for all that you do, I am proud to be a part of this inspiring community.

2021 UConn ECE Professional Recognition Award Winners

By Carissa Rutkauskas

The UConn Early College Experience (ECE) community and the University of Connecticut publicly recognize and thank outstanding instructors and administrators whose dedication and commitment help make UConn ECE successful. Those recognized have exceeded program expectations and excelled in preparing their high school’s students for the next level in their education.

The UConn ECE Professional Recognition Awards Show premiered on YouTube on Thursday, May 13 in front of a live virtual audience. Ten instructors and administrators were spotlighted in the production, as well as UConn’s Associate Vice Provost, Peter Diplock, and many UConn undergraduate musicians. Congratulations to the recipients:

Thomas E. Recchio Faculty Coordinator Award for Academic Leadership

Anthony Rizzie, Mathematics, University of Connecticut

Principal Award for Program Support & Advocacy

Frances DiFiore, Cromwell High School

Site Representative Award for Excellence in Program Administration

Ka Man (Mandy) Cheung, Fairchild Wheeler Interdistrict Science Magnet School

Instructor Award for Excellence in Course Instruction

Dr. Thomas Vrabel, Sustainable Plant and Soil Sciences, Trumbull Regional Agriscience and Biotechnology Center

Margaret Kimmett, Chemistry, Valley Regional High School

Lalitha Kasturirangan, English, Eli Whitney Technical High School

Library Media Specialist Award for Excellence in Enrichment and Collaboration

Liza Zandonella, Newtown High School

“Rookie of the Year” Award for Excellence in First-Year Course Instruction

Kelsey Kapalczynski, Statistics, Wethersfield High School

Christopher Wisniewski, Biology, Berlin High School

Jan Pikul Award for Continued Excellence in Instruction

Aaron Hull, Political Science, Greenwich High School