UConn Early College Experience recognized 10 outstanding UConn ECE Students this year, awarding each a $500 scholarship, which can be used at any institution. Winners are high school seniors, who have taken or are currently taking at least one UConn Early College Experience course and have excelled in the area in which they submitted their project. Learn more about the UConn ECE Student Scholarships on our Scholarships page.

Excellence in the Arts, Humanities, or Social Sciences

Winners demonstrate academic achievement and a potential for future academic and professional accomplishments in a field focusing on the Arts, Humanities, and/or Social Sciences.

Emily Tarinelli

Marine Science Magnet High School of Southeastern CT

Literary analysis essay: Feminism in the Absence of Independent Women

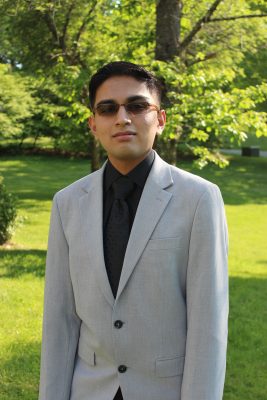

Ayushman Choudhury

Ellington High School

Rhetorically effective argument video: The True Cost of War

Kiersten Sundell,

Thomaston High School.

Portrait: Am I Next?

Excellence in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematic

Winners demonstrate academic achievement and a potential for future academic and professional accomplishments in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and/or Mathematics.

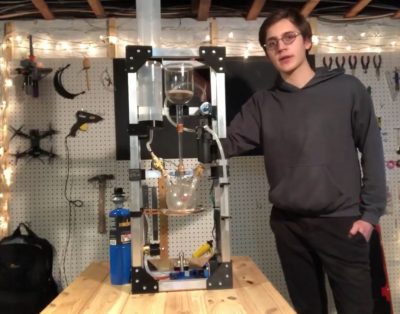

Conner Larocque

Hamden High School

Video: Autonomous Siphon Coffee Machine

Grace Pendleton

The Morgan School

Model: Gothic Cathedral

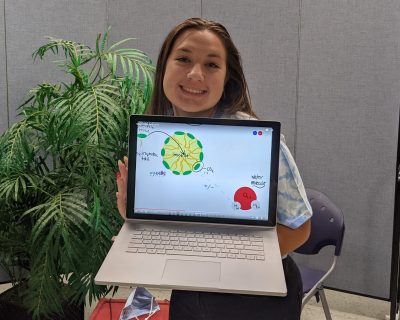

Emma Bator-Blanchet

Rockville High School

Video: How Soap Kills Coronavirus

Excellence in Civic and Community Engagement

Winners are academically successful, are already making a positive difference in their town or neighborhood, and are inspiring others to do the same. The students chosen for this award must be a UConn ECE Student who demonstrates ambition and self-drive evidenced by outstanding achievement in both school and their community.

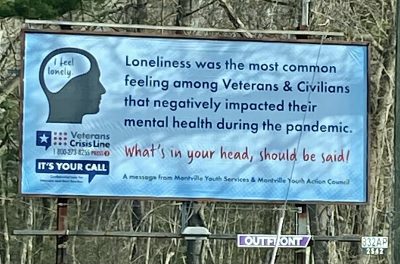

Stephen Duhamel

Montville High School

Development and promotion projects that strengthen peer interactions and wellness

Lindsay Haukom

Edwin O. Smith High School

Quaraconcerts, free virtual harp concerts offered to anyone who wanted happiness and human connection

Matthew Keating

Holy Cross High School

Co-founder of Step by Step, a nonprofit organization that helps the less fortunate in the community

Anirudh Krishnan

Ridgefield High School

Founder of the Ridgefield Music Mentors program